Gio Ponti (portrait)

“For life to be great and full it is necessary to put the past and the future into it” Gio Ponti

Giovanni Ponti, known as Gio Ponti, was born in Milan on 18 November 1891. During the First World War, he served in the Pontieri Corps of Engineers with the rank of Captain. In 1921 he graduated from the Milan Polytechnic. In 1928, he founded Domus magazine with editor Gianni Mazzocchi. It soon became one of the most important publications dedicated to the theme of contemporary living. He was the first artistic director of Fontana Arte. From 1936 to 1961 he was a tenured professor at the Faculty of Architecture at Milan Polytechnic, where he introduced the discipline of Interior Architecture. Considered the “last humanist architect” and one of the greatest architects and designers of the twentieth century, his work ranged from the design of buildings to interior design, from painting to the design of objects, furniture and furnishings. He moves freely between disciplines, thus breaking down barriers. A fundamental pillar in the architectural debate, he believes that architecture can improve people’s lives and cultural and social behaviour. He has left us, with his writings, one of the most conspicuous stylistic relics, in which constructive wisdom stands out, on the one hand increasingly modern and on the other a continuity of a classical tradition revisited through the filter of the avant-garde.

“His house always hosted famous people, from Eames to Wirkkala, from Rudofsky to Arata Isozaki, from George Nelson to Saul Steinberg and Alvar Alto etc.; while Nervi, Arne Jacobsen, Louis Kahn, Coderch etc. passed through his studio. What has always impressed me about Gio Ponti is his genius, his courtesy, his resolute and lovable character, his patience, his imagination and his versatility in all fields, from architecture to design, from painted drawings to images of ceramics, enamels, fabrics, from ironic forms to colours and glass. A Gio Ponti who was passionate about his craft and aware of its artistic possibilities, a champion of Italian architecture and a milestone in all Italian art of the 20th century.” Anna Querci (1)

(1958 – Turin – ADI members visiting Fiat – Photo courtesy: Book – Libro “L’Italia del Design” )

(1958 – Turin – ADI members visiting Fiat – Photo courtesy: Book – Libro “L’Italia del Design” )

In the 1930s, many companies with artisan origins changed course, involving architects and artists in the design of their production: Richard Ginori turned to architect Ponti, Ceramica di Laveno called on architect Guido Andlovitz, and Breda entrusted the interiors of its trains to Ponti and Pagano. “A “new” language giving a precise cultural and formal dimension to Italian industrial production”. (2) Confirmation of this is the impact of the first works for the Sesto Fiorentino ceramics company, presented at the Biennale di Arti Decorative in Monza, in international magazines and, in 1925, awarded the Grand Prix at the Paris Exposition des Arts Decoratifs. The ability to look at and reinvent domestic objects in a more evolved conception of use and form, the ability to design from traditional craftsmanship. His work and his influence in a number of Italian industrial realities set in motion the union between industry and art from which a new figure would emerge: the designer, a combination of artist and designer.

“A desire for light, for walls that reflect an iridescent mottled light, that vibrate throughout the day and night in the light. The white light is the (Newtonian!) conclusion of his decades-long passion and preaching for colours in architecture.” Luigi Moretti (3)

Some of the lamps he designed have become design icons: he collaborated with Fontana Arte (from 1931), with Lumen (1940), with Venini (1946), with Greco (1951), with Arredoluce (1957), with Lumi (1960), with iGuzzini (1967) and with Artemide (1969).

(1931 – “0024” hanging lamp for Fontana Arte – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Fontana Arte Catalogue. The Classics )

(1931 – “0024” hanging lamp for Fontana Arte – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Fontana Arte Catalogue. The Classics )

(1931 – “Bilia” table lamp for Fontata Arte – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Fontana Arte Catalogue. The Classics)

(1931 – “Bilia” table lamp for Fontata Arte – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Fontana Arte Catalogue. The Classics)

In 1933 he placed a rotating projector on top of the Torre Littoria in Parco Sempione in Milan. In 1936 Gio Ponti illuminates the Tower in Parco Sempione in Milan, on the occasion of the VI Triennale delle Arti Decorative e Industriali (AEM). In 1939 he integrates the lighting design into the architectural project of Palazzo Montecatini in Milan, in particular this relationship emerges in the entrance hall, a special attention to the electric light in the offices where he uses pendant lamps by Fontana Arte.

(1969 – “Gio Ponti 99.81” hanging lamp for Venini – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Giulia Chinello)

(1969 – “Gio Ponti 99.81” hanging lamp for Venini – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Giulia Chinello)

Gio Ponti, in 1949, takes Domus back into his hands, adapting to the times, starts publishing a column dedicated to industrial design, in particular a selection of English and American objects.

In 1950 he designed “illuminated ceilings” for Conte Biancamano. In “Dalla IX alla X Triennale” in Domus December 1951, Ponti reaffirmed two basic postulates: “Recognise as one of the most lively and topical problems the new relationship of collaboration between the world of art and that of industrial production” and “Reaffirm the unitary relationship between architecture, painting and sculpture”. (4) Concepts that we find in his projects. In 1952, he designed a luminous and illuminating ceiling for the ballroom of the Andrea Doria, Moto Nave.

The attention to the lighting technology aspect integrated with the architectural part, is manifested in his projects such as the use of fluorescent tubes for the lighting of Villa Planchart in Caracas, in 1955, highlighting the “suspended planes”. He had a preference for interior architecture, a protagonist in the dissemination of a new culture of living. In the same year he designed one of the city’s symbolic buildings, the Pirelli Skyscraper, a building that changed the skyline of post-war Milan, the first skyscraper to exceed the height of the Madonnina of Milan Cathedral.

In 1954 Gio Ponti was one of the members of the jury for the first Compasso d’Oro award. In 1955, a small group of architects, encouraged above all by Ponti, and two industrialists who were particularly attentive to the design of objects, began to meet to create a “movement” of “industrial designers”, the foundation of the ADI. “We do not have a wealth of raw materials, we have from history and vocation a good cerebral raw material. (…) This was a success of an Italian way of seeing things exclusively according to essentiality and purity, against those who consider them to be pandering to buyers’ tastes, interests that have nothing to do with any consideration of aesthetic value” Gio Ponti, in 1956, on the occasion of the awarding of the Grand National Prize of the Compasso d’Oro (1)

(1967 – “Pirellina” table lamp for Fontana Arte – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Fontana Arte Catalogue. Light)

This lamp, “Quadro di Luce”, made of enamelled metal and brass, was used for the Alitalia offices on Fifth Avenue in New York.

In 1969 Domus celebrates its fortieth anniversary. In the 470th issue of January 1969, Gio Ponti writes: “The merit is not ours but that of all the wonderful people we love, who love us, near, very near, far, very far, whose existence inspires us and whose attention encourages us, and for whom we continue to believe in man’s creative future, and to take part in the imagination.

45 Years of Domus

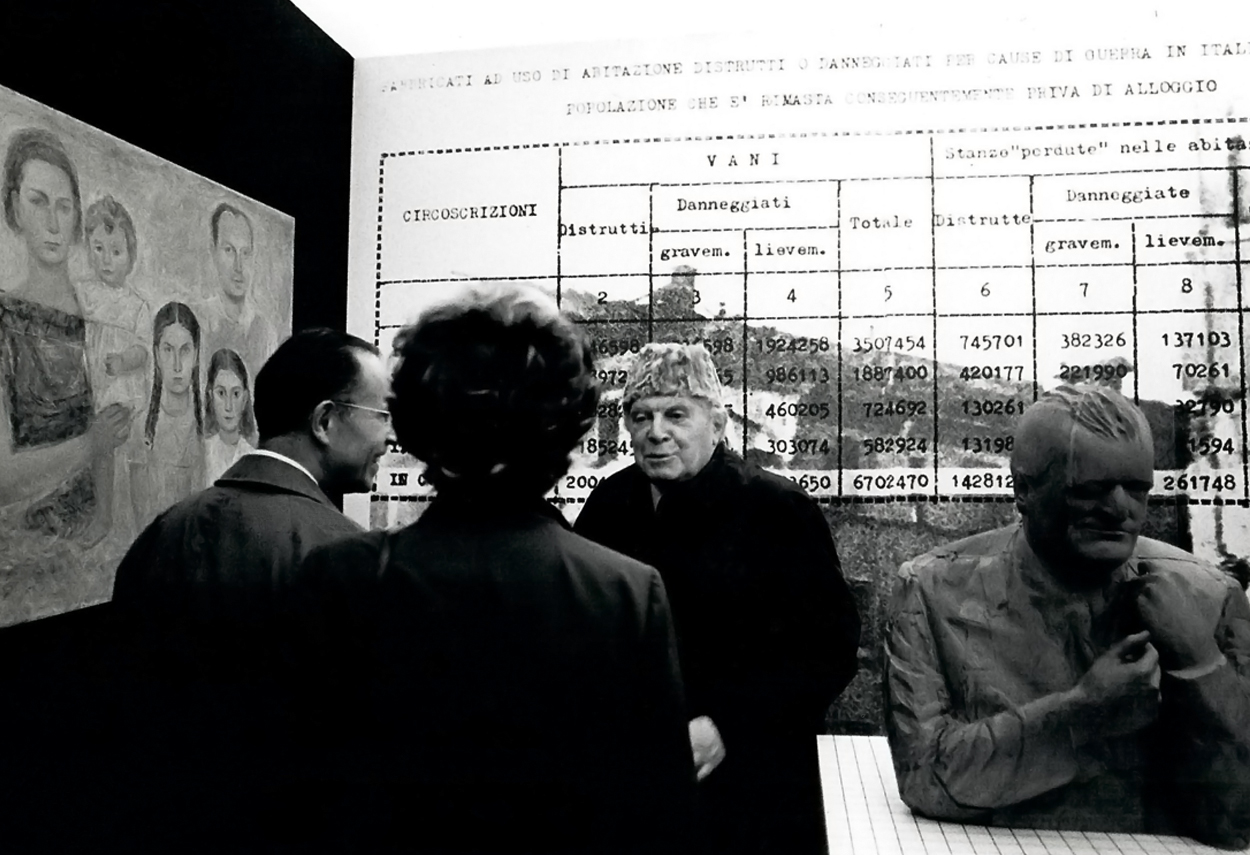

(1973 – France – Paris – Louvre Museum – “45 Years of Domus” – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1973 – France – Paris – Louvre Museum – “45 Years of Domus” – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

In the archives of Studio Castiglioni, we find Domus number 525 August 1973. On page 27 we find an article by Gio Ponti: “45 Years of Domus in Paris”. This title also appears in the “Exhibition” section of Architect Castiglioni’s projects. Together with his father Livio, he designed the audiovisual part and the general lighting of the exhibition. For Paris, Livio wanted to intervene with light, taking up the “basic technology” line and realising the Domus sign on the vault of the entrance vestibule while respecting the architectural structures without having to fix fittings, lamp holders, etc. He solved the problem with new light sources. He solved the problem with new halogen bulbs (35W/6 volt) with a very concentrated beam. He didn’t even want to use the old magic lantern (which is the modern slide projector). My instrument”, says Castiglioni, “is cheap and will last until the end of September: morning, afternoon and evening … excluding Mondays.

Ponti, in the first lines of the article, writes: “A public that, as far as we have been able to observe since the first days, has turned out to be mostly made up of students. (…) The interest of the students is what above all consoled us from the great effort.”

“While at the beginning Domus was bought by those who wanted to renovate and modernise their environment, their home, today the proliferation of furnishing magazines has changed things, and people buy Domus not so much to choose this or that type of lamp, chair or table, but to get hold of a global “package” of information on the level of different visual languages.”

(1973 – France – Paris – Louvre Museum – “45 Years of Domus” – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1973 – France – Paris – Louvre Museum – “45 Years of Domus” – Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

Gio Ponti, a multifaceted figure, combined design, the direction of Domus magazine and his many activities (painting, sculpture, etc.) with teaching. In an article written for the magazine Architetti in 1952, he deals with the theme “The problem of architecture schools”. Ponti’s view of the academic world is interesting. First of all he underlines a concept, also reiterated by Vico Magistretti and Piero Castiglioni: study never ends, it must continue uninterruptedly, with great curiosity, “The faculties of architecture must therefore become the very organism for the continuous updating of architects themselves.” Gio Ponti also stressed that workers, industries and public administrators should be “prepared for architecture” by means of cultural refresher courses organised by the architecture faculties themselves. He proposed an architecture faculty with open teaching, not involving only excellent professors, but with an annual programme involving great modern architects, professionals and specialists. If we think about it, this is the attitude taken by Ernesto Gismondi, who selected Milanese, Italian and international architects and designers as designers for his lamps. Ponti’s thinking on the transformation of architecture was avant-garde:

“This architecture will not have to have “a style” but, and this will be a teaching, it will only set to itself the terms of the exclusive functionality of teaching; and it will be thought adaptable to all developments. In form and spirit it will be the opposite of an academy. He wanted a visual school, constantly renewed and with equipment for photography, for modelling, indispensable for modern design, for lighting, here his sensitivity towards this technique emerges, as he specifies the necessity, the need to proceed with a project that evaluates both the day and night aspect of the building.” (5)

(1956 – Milan – Pirelli Skyscraper– Gio Ponti – Studio Valtolina-dell’Orto – Arturo Danusso – Pierluigi Nervi – Photo courtesy: Book “28/78 Architettura” )

(1956 – Milan – Pirelli Skyscraper– Gio Ponti – Studio Valtolina-dell’Orto – Arturo Danusso – Pierluigi Nervi – Photo courtesy: Book “28/78 Architettura” )

This aspect is also dealt with in the chapter “Ancient architecture by night” of the book “Amate l’Architettura” written in 1957 by Gio Ponti: “In these nocturnal conversations between stones and moonlight, Architecture returns to the framework of the silent things of nature, the signs and everything that concerns humans disappear (…) What remains is the solemn ecstatic song of the stones, “nocturnal”, architectural, and the arcane play of shadows on the surfaces”.

By virtue of electricity, architecture gives life to a new nocturnal scenario, new aspects, new volumes in space, “luminous spatialities” and “luminous appearances”. Lighting is defined by Ponti as a constitutive element of architecture. Electricity, with lifts, made buildings grow taller, with telephones and radio, it put all dwellings in contact, thus transforming architecture. Light has brought an evolution, it has changed the ways of living, of experiencing the city, changing its night-time appearance. Light, which used to be in the form of a flame, kept isolated to prevent fires, now “runs” wherever we want, through luminous ceilings, indirect lights, lighthouses that illuminate elevations. Light simulates shapes, cancels certain perceptions of distance and dimension because it lacks depth, it cancels and transforms weights, substance, volumes, modifying perception. (6) Another important aspect of Ponti’s thought is the break between interior and exterior space. He affirms “Architecture from the outside penetrates the whole”, maintaining that living space is not a composition of closed boxes, but built with spaces that interpenetrate, that dialogue with each other. This concept, which cancels the border between inside and outside, can be found in the design of the fourth tower of City Life by Bjarke Ingels Architect.

Bibliography

(1) “L’Italia del design”, Alfonso Grassi e Anty Pansera, 1986, Marietti Editore, Casale Monferrato

(2) “Gio Ponti designer”, Laura Giraldi, 2007, Alinea Editrice s.r.l, Firenze

(3) 28/78 Architettura, by editoriale Domus, Milano, printed in Italy 1979

(4) “Storia e cronaca della Triennale”, Anty Pansera, 1978, Longanesi & C., Milano

(5) “Architetti”, Direttore Rivista Giacomo Piccardi, 1952, Editrice Architetti, Firenze

(6) “Amate l’Architettura”, Gio Ponti, Vitali e Ghianda, 1957, Genova

Other Posts