Franco Albini (portrait)

“Air and light are the building materials” Franco Albini

The Franco Albi Foundation describes him as ‘A silent, rigorous, ironic man, Albini worked tirelessly, supported by a moral code that accompanied him throughout his career. He firmly believes in the social role of the architect as a profession serving the people. He considers it the very reason for his existence’. (1)

Born in 1905, he was one of a group of young architects who saw architecture as a mission to build the city of the future. As Vico Magistretti recalls, “We kids were discussing on an equal footing with the greats of the Modern Movement in Milan, such as Lingeri, Gardella, Albini, with a Milan that was bursting with energy”. The relationship between architecture and design, with its methodical approach to each piece, thus brings the precision of design into architecture. “Starting from the detail and making it become the idea of the whole” Marco Albini. Vittorio Gregotti says that Albini taught him that the simple word is a very complicated thing. Renzo Piano describes him with the words “school of patience”, a “school of silences”.

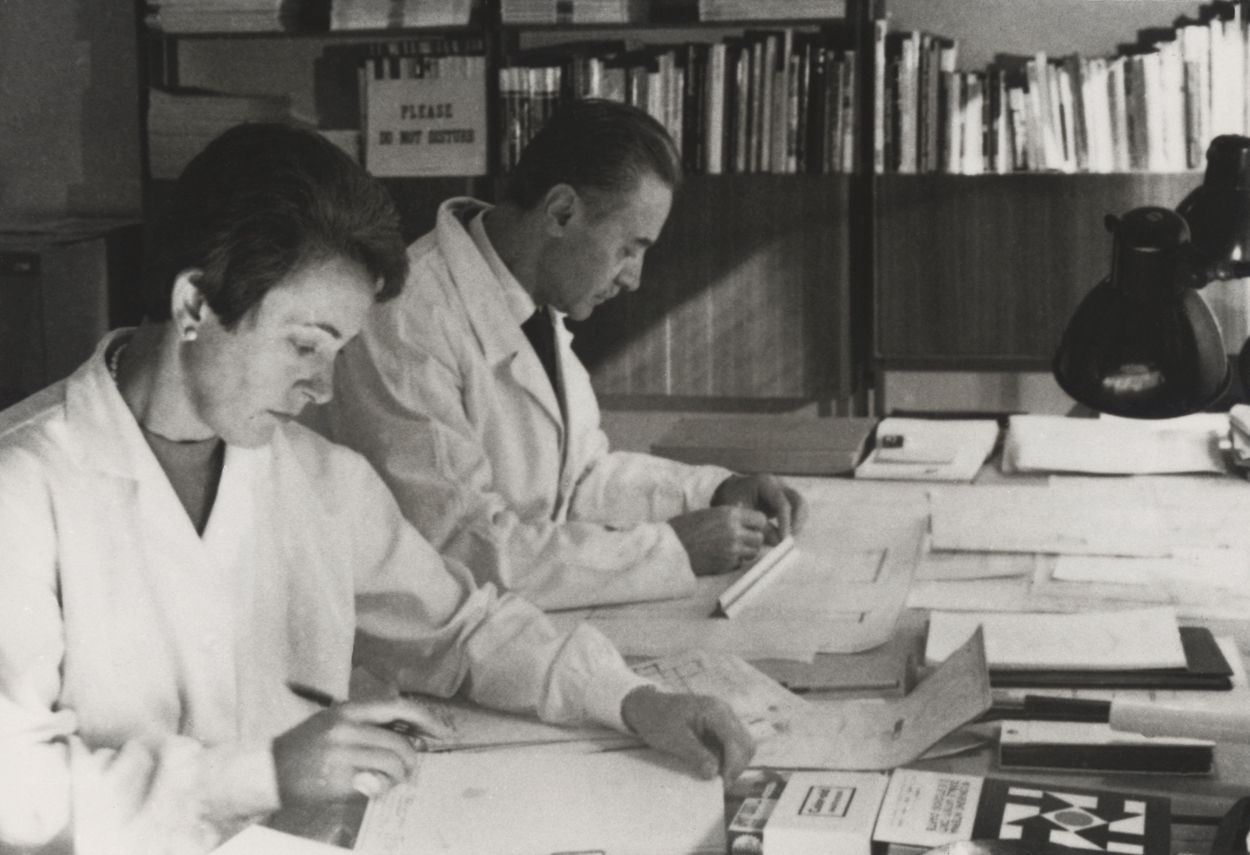

(Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

He graduated in Architecture from Milan Polytechnic in 1929. He began his professional career in the studio of Gio Ponti and Emilio Lancia, with whom he worked for three years. He worked on social housing and took part in the competition for the Baracca district in San Siro in 1932. In those years Albini worked on his first villa (Pestarini), which Giuseppe Pagano, an architect and critic of the time, described as follows: “This consistency, which the superficial rhetoric of fashionable jugglers calls intransigence, and which is instead the basis of understanding between the fantasy of art and the reality of the profession, in Franco Albini, is so deeply rooted that it transforms theory into a moral attitude”. But it is above all in the context of exhibitions that he experiments with the compromise between that “rigour and poetic imagination” of which Pagano speaks, coining the elements that will be a recurring theme in all the declinations of his work – architecture, interiors, design pieces. Albini is a complete designer, whose work ranges from construction to design, from installations to town planning. Since 1949, he has been teaching at universities in Venice, Turin and Milan in addition to working as an architect. Since the early 1950s Franco Albini has worked with Franca Helg. The “Grand Dame of Architecture” was one of the first female personalities to design, create and innovate ways of living. An important figure in twentieth-century architecture who managed to impose herself with authority, determination and elegance in a purely male professional context. (2) As Cini Boeri‘s experience testifies, a Vogue article recounts that the words of architect Giuseppe de Finetti try to discourage her. Albini is a famous interpreter of the rationalist current, a movement whose aim is to improve people’s quality of life through design. He is a member of Ciam, Inu, Academico di Santa Lucia, an honorary member of the Hague and a member of the Scientific Institute of the CNR. He participates in numerous international congresses and commissions on the problem of modern museography, giving lectures at various national and international institutions. (3)

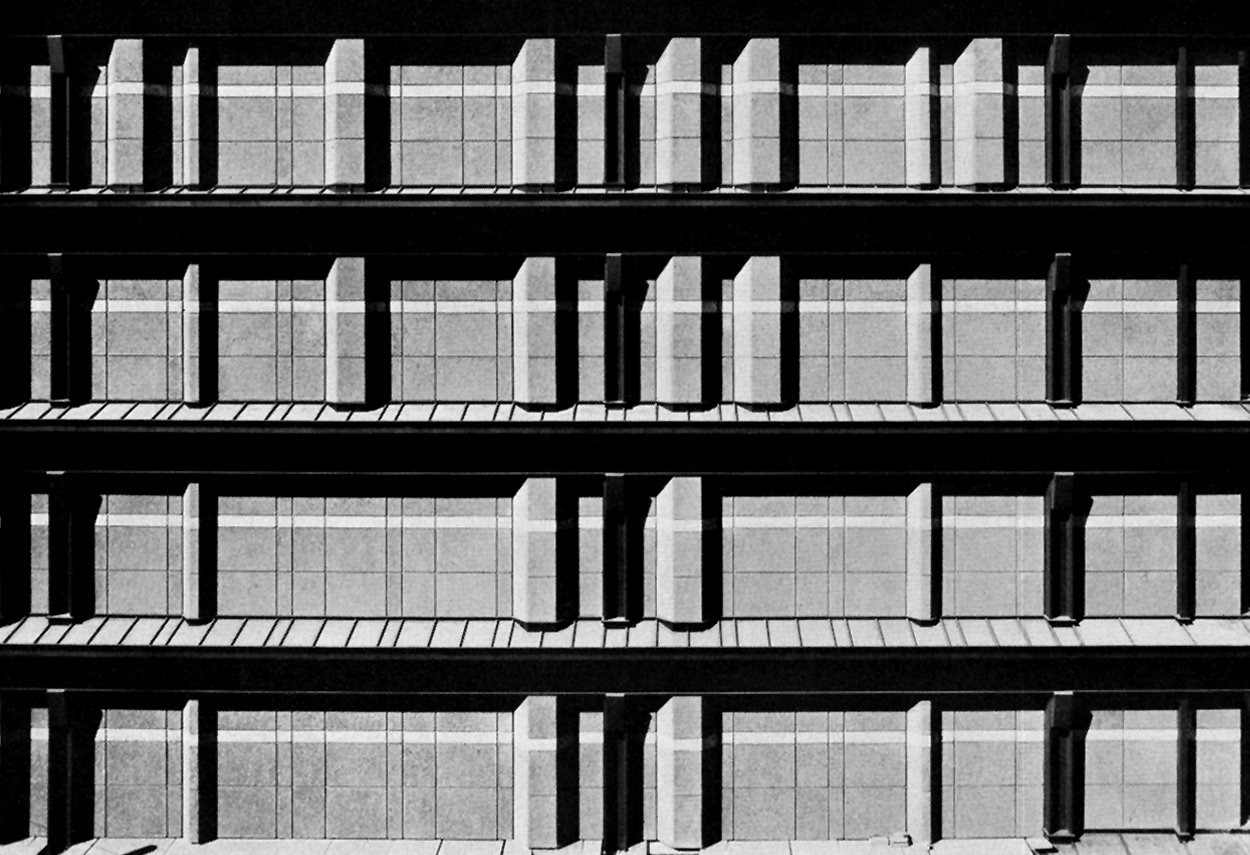

In 1964, Franco Albini, Franca Helg and graphic designer Bob Noorda won the Compasso d’Oro award for the Milan Underground signage and fitting-out (1962-1966), defined as a great work of social design.

Motivation of the jury: “Awarded for the particular qualities of the architectural coordination and organisation of the signage of the new Milanese Metro stations. These qualities can be summed up in the effort to directly qualify, through communication, the architectural environment; in the in-depth study of the set of signs, of their hierarchical relationships, of their location; in the technological and dimensional organisation of the internal surfaces of the various environments, aimed without impoverishment at unifying the various elements; in the counterpoint of the materials”. (4)

Since 1977, after the death of the great master, the Studio has been working with Franca Helg, Antonio Piva and Marco Albini.

“Details make perfection and perfection is not a detail” Leonardo da Vinci

The Luisa armchair won the Compasso d’oro award in 1955, and is present in the permanent collections of the: Moma in New York and at the Design Museum of the Triennale in Milan. Today produced by Cassina.

(1950 – “Luisa” armchair for Poggi – Franco Albini – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1950 – “Luisa” armchair for Poggi – Franco Albini – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1952 – “Fiorenza” armchair for Arflex – Franco Albini Photo courtesy: Arflex)

(1952 – “Fiorenza” armchair for Arflex – Franco Albini Photo courtesy: Arflex)

(1957 – “LB7” bookcase for Poggi – Franco Albini – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1957 – “LB7” bookcase for Poggi – Franco Albini – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

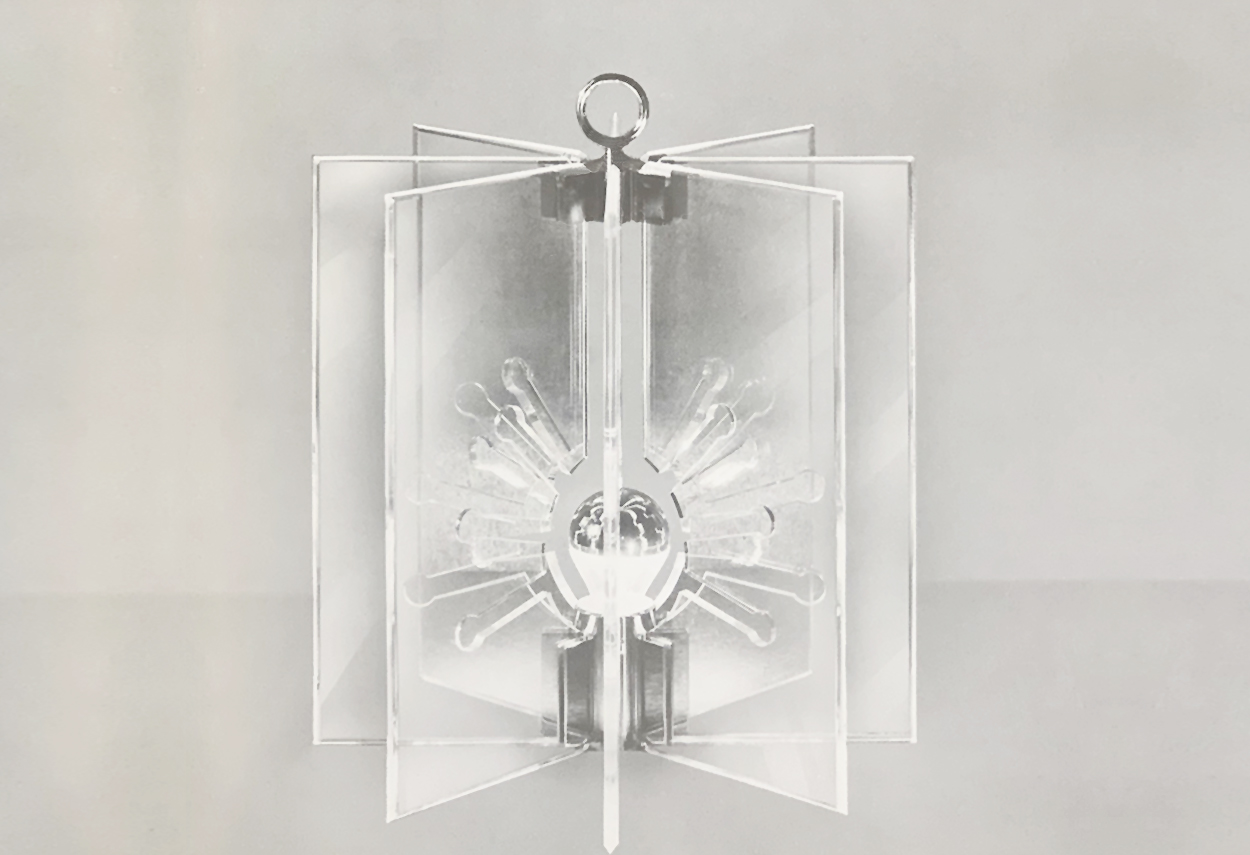

In 1963 Albini-Helg designed the table lamp model “524” for Arteluce, a company owned by Gino Sarfatti. Eight diffusing elements of transparent perspex form a segmented structure that can be held and moved by means of a chrome-plated metal ring. The new materials make a decisive contribution to the lighting sector.

(1938 – “Mitragliera” Floor Lamp – Franco Albini – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1938 – “Mitragliera” Floor Lamp – Franco Albini – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1963 – Table lamp “524” for Arteluce – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Photo courtesy: Arteluce Catalogue)

(1963 – Table lamp “524” for Arteluce – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Photo courtesy: Arteluce Catalogue)

In 1968 Franco Albini, Franca Helg and Antonio Piva designed a series of lamps “AM/AS” for Sirrah. Sirrah (whose name comes from a shining constellation) is a lighting company founded in Imola that made its debut at the 1968 Milan Triennale with a series of lamps designed by Albini-Helg-Piva. Thus began a collaboration. Acquired in 1994 by iGuzzini. The series of lamps is characterised by the particular connection of the diffuser with a universal clamp and by an extreme modularity, so that with just a few elements it is possible to create various floor, table, suspension and wall models. The “AM2Z” and “AM2P” models elegantly redefine bases, floor lamps and, above all, the two historical versions of the diffuser, the semi-sphere and the goblet. (5) The series has been produced by Nemo Lighting since 2008.

(Table lamp “AM1N” for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

(Table lamp “AM1N” for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

(AS41C” hanging lamp for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

(AS41C” hanging lamp for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

(AS1C” table lamp for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

(AS1C” table lamp for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

(AM2Z” floor lamp for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

(AM2Z” floor lamp for Nemo – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Antonio Piva – Marco Albini – Photo courtesy: Nemo)

The design often starts with a simple detail that only appears to be independent, but which must be able to be assembled perfectly with all the other elements according to “one logic”. It starts with a rigorous study of the individual pieces and arrives at the overall design. This way of proceeding is applied to all types of work: from the simple production of design objects to the design of buildings. Projects include Villa Pestarini in Milan (1038), the “Fabio Filzi” district in Milan (1936-1938), the project for the restoration of Palazzo Rosso in Genoa (1952 – 1962). “This is the case of Albini in Palazzo Bianco, in Palazzo Rosso and its Convent of San Agostino in Genoa, or in the later Museo Civico degli Eremitani in Padua. The encounter between the existing and the new is resolved with extreme rigour and refinement, creating a balance, where, on the one hand, one can feel the hand of Albini Designer in the museographic layout, on the other hand the natural “style” of the furnishings does not disturb the works on display and the nature of the existing architecture”. (6)

The setting up of the Salone d’Onore for the 10th Milan Triennale (1954), La Rinascente in Rome (1957-1960), Olivetti shop in Paris (1958), Sant Agostino Museum in Genoa (1963-1979), the New Luigi Zoja Spa in Salsomaggiore (1964 – 1967).

(Rinascente in Rome – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(Rinascente in Rome – Franco Albini – Franca Helg – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

Bibliography:

(1) http://www.fondazionefrancoalbini.com/franco-albini/

(2) https://www.corriere.it/bello-italia/notizie/cento-anni-fa-nasceva-franca-helg-gran-dama-dell-architettura-2002a428-83f6-11ea-ba93-4507318dbf14.shtml

(3) Anty Pansera, Dictionary of Italian Design, Milan, 1995, Cantini Editori

(4) https://www.adi-design.org/upl/CdO_STORICO/CdO%20storico%20MOTIVAZIONI/Motivazioni_1964.pdf

(5) Alberto Bassi, La luce italiana, Milan, 2003, Electa

(6) Giorgio Muratore, Alessandra Capuano, Francesco Garofalo, Ettore Pellegrini, Guide to Modern Architecture, Bologna, 1988, Zanichelli

Other Posts