Ettore Sottsass (portrait)

“The rite of architecture is performed to make real a space that was not real before the rite. Space is real when it is solid with attributes and heavy with meanings, when it is condensed – like a broth – of presences and suggestions, when it drips – like a dense colour – of surprises and transformations, when it pales with shadows and corrupts with light (1956)”. (1) Ettore Sottsass

After graduating from high school, he attended the Faculty of Architecture at Turin Polytechnic, where he graduated in 1939. In 1947 he opened his own studio in Milan, after working with Giuseppe Pagano. In addition to his passion for art and design, he also devoted himself to photography. In 1957 he became art director of Poltronova, for which he designed the “Superbox” – wardrobes inspired by road signs or petrol stations – “Barbarella” (1965) and the “Ultrafragola” mirror (1970).

In 1958 he began a long collaboration with Olivetti, as a design consultant, which led to numerous awards, including three Compassi d’Oro. For the Ivrea-based company he designed, among other things, the first Italian electronic calculator, “Elea 9003” (1959) and many typewriters. (1959) and many typewriters, including the ‘Praxis’ (1964), ‘Tekne’ (1964) and the famous ‘Valentine’ (1969, with Perry King).

(1969 – “Valentine” typewriter for Olivetti – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1969 – “Valentine” typewriter for Olivetti – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

Emilio Ambasz chose him to represent the new Italian design at the MoMA exhibition entitled “Italy. The new domestic landscape” in 1972. On an evening in 1980 in Ettore Sottsass’s living room, where a group of young designers and architects were staying, Memphis was born. “(…) as an urgent need to reinvent a way of doing design, of envisaging other environments, of imagining other lives” (2) Barbara Radice

(1981 – “Ashoka” Table Lamp for Menphis – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1981 – “Ashoka” Table Lamp for Menphis – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1981 – “Treetops” floor lamp for Menphis – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1981 – “Treetops” floor lamp for Menphis – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

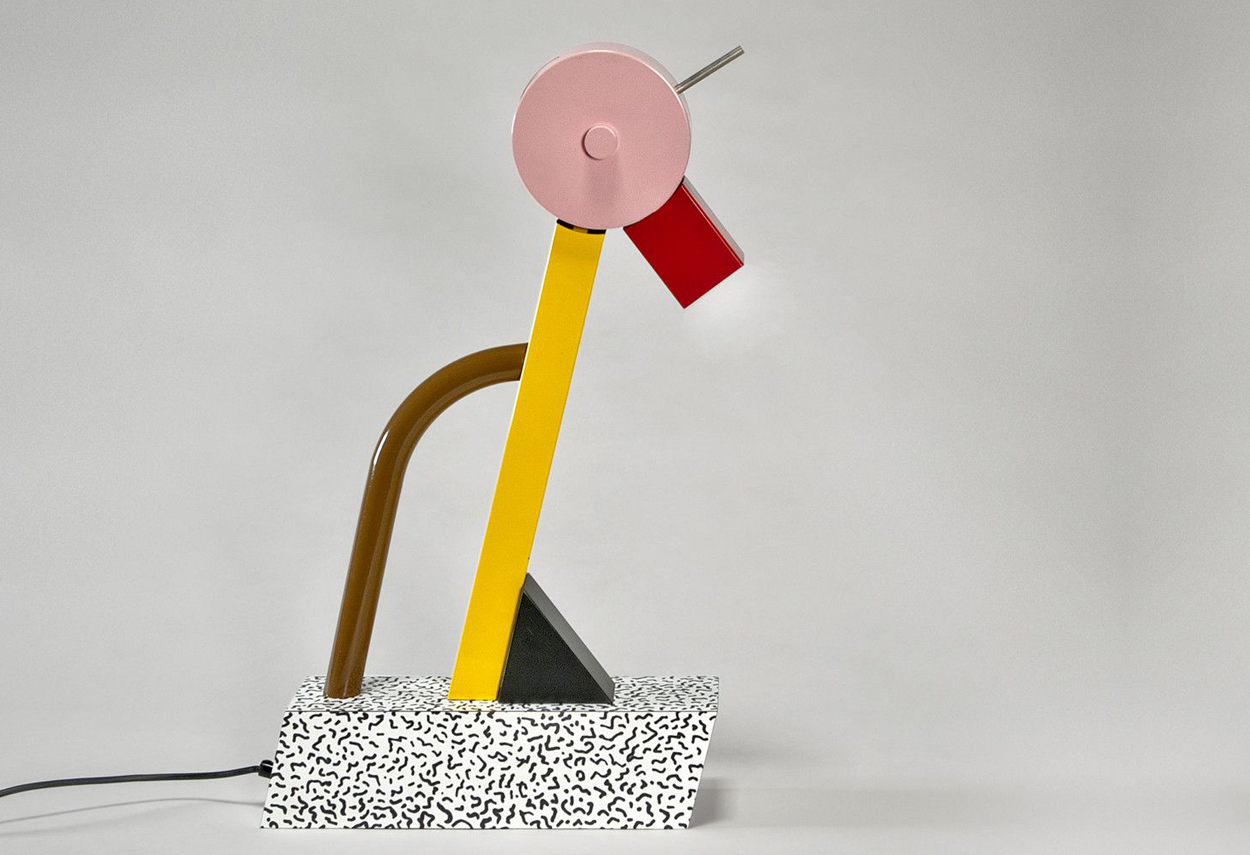

(1981 – “Tahiti” table lamp for Menphis – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1981 – “Tahiti” table lamp for Menphis – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1981 – “Callimaco” floor lamp for Artemide – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

(1981 – “Callimaco” floor lamp for Artemide – Ettore Sottsass – Photo courtesy: Pinterest)

And what are you doing in Italy?

The interiors for “Malpensa 2000”. the project for Alitalia’s VIP lounges around the world, and then I’m also doing my own thing…

What do you mean by “your stuff”, is there a difference?

Of course, as you can see, this studio is a bit like a factory with lots of jobs and lots of people working, but it’s not a factory, or rather we’ve tried to make sure it’s not. It’s important to develop a pleasant group policy, there’s no clocking in or out, we’re on a first-name basis and on every project we try to create intensity and enthusiasm; then of course there are those who count the most, but there are no ‘bosses’, I believe that authority does not derive from hierarchies… so it seems to me that this is neither a factory nor an industry. We do not work for turnover or income but to do projects well enough.

In such an enlarged dimension of work, what does quality become, how can it be controlled?

I spend about four hours a day looking at and discussing projects that others follow in detail, discussing and saying this is fine, this can be changed, etc., etc., and in my opinion we manage to carry out projects of fairly high quality because, first of all, my partners are all very good and culturally homogeneous, i.e. we know where we want to go culturally and politically…

Is it a problem of style?

No, it’s a problem of method, even if style is also a method of communicating…

When you talk about “doing your own thing” what do you think about?

There are the small projects that are more private but not minor. I do exhibitions, the usual furniture, glassware, objects, my own drawings, and now I’ve also become a photographer, which is what I’ve always done, but now someone has decided that I’m not just an architect and designer but a real photographer, and they call me, ask me to do exhibitions and books… It’s a bit of a frenetic activity, almost an obsession, because, you know, in the end even doing a book is a communication project where you have to decide a lot of things… then there’s “TERRAZZO”, which Barbara (Radice) does, where we decided to end up as a magazine but how to continue as a publishing house with a series of… “subtle” books, a bit chic, a bit snobbish.

How did you approach the subject of the airport at Malpensa?

As a traveller. I tried to think of a place that would accompany and somewhat console the anxieties of both arriving and departing travellers. The departing traveller is always a little anxious… you know, if I’m sitting here I’m more relaxed than if I’m sitting ten thousand metres away; and the arriving traveller is tired, pissed off, fed up… etc. And above all I tried to avoid the idea that the airport is drawn as a metaphor for an organisation. Because the theme is actually to accommodate a man who is more or less tired, more or less agitated, so that he calms down…

And how did you avoid the clichés of the airport metaphor?

For example, I banned the use of stainless steel as much as possible, so it’s either wood or fabric, and if it’s laminate we invented a laminate with Abet that looks like paper but has impurities inside it that give it a bit of depth, which doesn’t have that icy compactness of laminates; and the idea came to me from a packet of paper that arrived from Japan…

What about the lighting?

We have tried to make suggestions for differentiation. I don’t understand why at airports you have to feel like you’re on a theatre stage with lots of light when you might want to have some shady places to read while you’re waiting. We tried to differentiate and also to cancel reflections by using opaque materials and surfaces… stones.

What reference model did you take?

The hotel lobby, of certain hotels… because I feel very bad about airports like Munich or Vienna, like those things Foster does, full of welded tubes, of crystals, because I don’t see the need to insist on technological metaphors that don’t calm anyone, while an airport that was all like a Stube with a glass of beer or a goulash… well, I would understand it better. In the end, I wish airports didn’t exist at all, I mean as an institutional type, I would like to be able to take the plane like the bus, I know it’s difficult but I can try… excuse me a moment … (…)

If you like from your Austrian childhood in the woods. Perhaps one of these metaphors we feed on is that of nature, of the concept of the natural, which is increasingly a kind of mythical, utopian value, because in reality we are surrounded by and rely on an almost entirely artificial universe.

Yes, this is true for us west-metropolitans; if you go to China or India, you see more of the sky, and even in the big cities contact with light, temperatures and smells is not so mediated; we live almost constantly in lights, temperatures, smells, materials that have been designed, constructed, manipulated, so it is difficult to talk about ecological design, and I don’t really know what that means, which is to say I understand it, but I would say to those who talk about it that it would be better to talk about it to armies, not to designers. Because we consume very little of the planet… just think of what an aircraft carrier is, think of the ecological destruction of a war or those four atomic bombs in Polynesia… then it is true that we have to think about it, but it is a planetary political problem about which we designers can do very little.

Aren’t you optimistic?

I’d say I’m more of a fatalist, even if being fatalist means being a bit of an optimist. I am a fatalist in the sense I was saying before; in the meantime we are conditioned by our births, our upbringings, our places, our origins. The fact that my father studied in Vienna and was full of German books on architecture, I feel it is a heavy, almost fatal conditioning; I wasn’t born in Polynesia and I used to catch fish with my hands. We always think too little about the strength of the cultural conditioning of time and space. And it is precisely on these conditions that we sometimes develop the deformations that are projects. When we get excited about the Ginza and the neon lights rather than the multicoloured plastics, it is because we want to work on these conditionings in some way. And that’s also why every now and then I have to go out of my box a bit and detoxify.

That’s why the only house you’ve ever bought is in Filicudi in the middle of the Mediterranean….

Near a volcano that’s a few million years old, difficult to reach, without water, they bring water… basically it’s an artificial island; until yesterday it didn’t even have electricity and now that it does we have to get used to it, it almost bothers us, this dazzle. Because you get used to the fact that the light goes down with the sun and then it’s gone, and then you use candles or acetylene to create small areas of light beyond which there is darkness, half-light, and it’s a crazy experience, the space changes and you learn new things.

What did you learn?

In some cases to use very little light. For example, we did an exhibition in Maastricht of African sculptures from the Dresden museum, an extraordinary heritage. And I thought that they shouldn’t be looked at the way we are used to looking at sculptures, because they were ritual instruments, and in Africa when they made them there weren’t neon tubes or anything like that; so I made some dark rooms and put thin nets in front of the display cases so that you could only see the sculptures when you were in front of them, they were apparitions that came out of the dark in a state of mystery… these observations can be made if you learn to use darkness as a complement to light. Light cannot be analysed mathematically, it is not a number, it can change your perception and the quality of materials, colours, space…

Dialogue between Ettore Sottsass and Franco Raggi (2)

There is a beautiful phrase: ‘Light creates atmosphere, light creates the feeling of a space, light is also the expression of structure’. These words are from Le Corbusier. In one of his buildings – Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp – he put this concept into practice, using the relationship between light and shadow. Architectural Lighting design must take into account the dialogue between light and shadow.

I too went to visit him. I like to remember him with some of the words he said to me about shadow, one afternoon at sunset; and with other words he had written years before about light, but the light of the moon. (3) Franco Raggi

I like the word shadow very much because “shadow” in a certain sense means mystery, uncertainty. Of course shadow is not darkness. But mysterious things happen in the shadow and it is the shadow that gives us the dimension of space. I’ve realised that when I make a drawing, even a small one, let’s say of a chair, any nonsense, I always put the shadow. If I don’t draw the shadow there is no third dimension. I don’t want to make comparisons, but even Picasso used them. Then there are surfaces, monuments, architecture, which are made of shadows, you can see them by looking at the shadows. (August 2007)

It’s not the opposite of shadow … I think, and it’s important that there’s not too much of it. It’s again the problem of allowing ambiguity, of not giving definitions. I have never thought of light alone. (August 2007)

Countless works of architecture, houses, palaces and temples have been built with shade in mind. A dark penumbra that immediately becomes a visible and real metaphor for the impenetrable structure of existence. It is enough to venture into these immense volumes of architecture filled with countless gigantic columns to understand/feel that darkness becomes the absolute mystery of existence. A place of fear and protection. Final image of reality. (1989)

(in Filicudi) … when there is a full moon, as there was on the night of 28 July 1988, a strange and magical light comes over the island. The houses and terraces whiten as if it were daylight, the meadows become mother-of-pearl and the caper bushes, carob trees, wild olive trees and eucalyptus trees become black holes like caves and no one knows who lives there. On the island of Filicudi, on some nights of the year, the moon is a powerful cold lamp; it is of little use to men (perhaps it is of use to lovers who dive naked into the shimmering water) but it is of use, I think, to wild rabbits, perhaps to mice, perhaps to owls or perhaps to snakes. Dogs certainly don’t like the full moon; they fill the island’s silence with restless barking. What one might think, however, is that the houses on the island are not designed to receive light from the full moon. As I have already said, during the hours of the full moon, almost all the men and women are tired and play half-dead in their beds or in the beds of others, and they make little, if any, use of the moon. Therefore, the architecture of Flilicudi is not designed to receive and control the light of the full moon. Besides, to tell the truth, even speaking in general, I know little about architecture designed for the cold light of full moon nights, and I know even less about architecture designed for nights of galactic light, I mean for nights illuminated by that impregnable light, by that light without shadow that sends down the starry skies … (from “La Luce della Luna” published in Terrazzi n°2, 1989) (4)

Bibliography:

(1) https://www.domusweb.it/it/progettisti/ettore-sottsass-jr.html

(2) Alberto Bassi, La luce italiana, Milan, 2003, Electa

(3) Courtesy Franco Raggi: Dialogue between Ettore Sottsass and Franco Raggi – 22 February 1996

(4) Courtesy Franco Raggi: Thoughts of Ettore Sottsass collected by Franco Raggi published in Flare – Architectural Lighting Magazine – n°47 – September 2008 – page 116

Other Posts