Livio Castiglioni (portrait)

In this section we have mentioned some of the great masters of design, lighting design and architecture. Livio Castiglioni has collaborated with most of these figures. The Studio in Via Presolana 5 came to life with him even though this “craft workshop” (where architectural lighting was born) can communicate through inventions, projects, lighting fixtures, lighting technology, the historical archive, …, we tell about the Great Master through the words of Chiara Baldacci. In 1997, on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of Livio Castiglioni’s death, she wrote this article.

“Researcher in light and sound communications, architect, industrial designer, lighting designer, lighting specialists, expert in audiovision and audio kinetics” was how Livio Castiglioni was defined in the introduction to an interview he gave to Silvia Giani in 1974, where he stated, among other things: “Serial design interests me from a technological point of view because the designer, in my opinion, if he has to design a camera, must also be a photographer”.

(1974 – Milano Casa – Dialogue with Silvia Giani – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1974 – Milano Casa – Dialogue with Silvia Giani – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

In short, there is integrated design and there is formal design: by integrated I mean that to make a design you have to know how it works, the technological methods of construction, make a psychological examination of the user and at the end, after I know these things, the line comes out. But I don’t think it’s serious to make a design only from the formal point of view, I’m not interested in the so-called re-design. Above all, it is the designer who has to lead the manufacturer on the right path. I have to say: I won’t make your design if you don’t allow me to analyse how you build it and if you don’t give me 500,000 lire to give to the psychologist or … the orthopaedist. Instead they make designs one after the other, so …”.

Born in 1911, he has been an amateur radio operator since 1930. It was a passion that accompanied him throughout his life, which led him to place antennas all over the place, to transform his small cars into real two-way radio stations, which allowed him, with his “ci qu, ci qu”, to keep in touch with half the world, even from the most impervious alpine shelters. After attending the Faculty of Engineering for some time, he graduated in 1936 with a degree in Architecture from the Regio Istituto Superiore di Ingegneria in Milan, which later became the Politecnico. He opened his first studio in Milan with Luigi Caccia Dominioni. (…)

(Stick and hat – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(Stick and hat – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

“Wrapped in a black cloak, the Borsalino well fitted, glasses “protagonists” in his face, the cane to complete the whole, in the background of the floor of Bobo Piccoli at the entrance of the Palazzo delle Stelline in Milan in Corso Magenta”. This is how Anty Pansera remembers it as she continues her story.

“The path chosen by Livio, in fact, has always transcended the commonly understood object of use and already at his debut, in 1936, the year of his graduation, we meet him in the Milanese Palazzo dell’Arte on the occasion of the VI Triennale engaged in ordering the Hall of Italian Priorities in Art where he had chosen to communicate with visitors by a fantastic way: “The veil of light that descends from above, from the cut marked in the ceiling to the strip of earth traced below the floor level, illuminates the plastic elements that express the topics dealt with. (…) An ante litteram minimalist, a lighting designer before the term (and concept) of design was even established, Livio Castiglioni always aimed to build environments with light, to give it form and play with its effects rather than designing lamp objects; to create spaces with sounds, “piloting” their listening rather than designing radio equipment. Certainly not to be forgotten are two products of great significance, two archetypes that are due to him: a radio set and a lamp. Designed with Pier Giacomo and Luigi Caccia Dominioni, the now legendary Phonola radio was exhibited at the exhibition they curated and dedicated to radio equipment at the 7th Milan Triennale and is the first radio receiver (table and wall mounted). The Boalum, designed with Gianfranco Frattini in 1971, is an archetype and is an unusual free-form light object, a sculptural object. (…) Protagonist of the advent and affirmation of the luminaire / technical instrument, detached from the traditional placement among the components of furniture. In 1972, Livio and his son Piero began to use the bare halogen lamps that Fontana Arte was to produce in 1983 under the name of Scintilla, a modern lighting system that turned a room into a lighting fixture”.

Anty Pansera

(1972 – Cussino – Caricature Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1972 – Cussino – Caricature Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

Here are some of the testimonies and memories of Livio Castiglioni’s friends and collaborators.

“My encounters with Livio Castiglioni were many, but unfortunately they are somewhat veiled from my memory by the passing years. They were challenging meetings when, in Augusto Morello’s house in Piazzale Libia, we talked about design: we were in the early 1960s. So, as a living historical memory of Italian design, I can only remember him as a designer full of innovative enthusiasm for telephones, radios, light bulbs, wires and fireworks. They were also meetings of games and pranks: I remember a terrible one, organised in his home on Via Morosini when, with ingenious telephone connections, we got a mutual friend up and down the street in the middle of the night with the mirage of a holiday prize, which then regularly went up in smoke, leaving him desperately waiting on the pavement in vain. Few business meetings, too bad! With Gianfranco Frattini for the creation of lighting products for a hotel in Capri, which Kartell did not complete. I close my eyes and I can still see him in front of me with his wide-brimmed black hat and his personal myopic glasses. Hello Livio”. Giulio Castelli, engineer

“He arrived with his wide-brimmed hat, his face smiling (always). Creative and affable, with a picturesque bohemian allure – and a communicative humour. At the time, I was in charge of Osram communications and Alberto Mornacco, my collaborator for the entire trade fair and media sector, introduced me to him. A very challenging task, the first large Osram pavilion at Intel in 1975. At the inauguration, the 220 square metres of the pavilion, all open, were lit by an innovative system with “bare” halogens, “Scintilla”, put in place for the first time at a major international exhibition. A sky of stars, a real party. Livio, who is in love with light, just like his son Piero, had no choice but to create it”.

Giorgio Antonelli, journalist

(1977 – Intel Osram Pavilion – Livio and Piero Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1977 – Intel Osram Pavilion – Livio and Piero Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

“I have two special memories of Livio. When I was designing the headquarters of the weekly magazine “Espresso” in Rome, I asked Livio who, with his usual willingness, immediately accepted willingly, if he wanted to take care of the lighting. I had known him for a long time, but it was from then on, working together, that I got to know him better and understand what a “phenomenon he was”. I say “phenomenon” because you don’t often meet a simple and straightforward person, a non-conformist, an artist, an inventor of new technologies, a refined dandy, a great humourist, all rolled into one. When we visited the site in Rome, I had my first glimpse of the ‘phenomenon’ when I saw him – wearing a wide-brimmed black hat, a white scarf over his impeccably tailored dark suit and a thin bamboo stick, which he fiddled with as he strolled through the rooms among the workers, suppliers and client representatives who looked on in amazement and admiration – listing exactly the right type of lamps to use, often inventing new solutions on the spot. For example, a new lamp holder to solve a problem in certain specific situations. It goes without saying that the end result was a great success for both of us. I got another shock when, in Milan, we found ourselves in his ‘study-workshop-storage-office’, which was fascinating in its ‘tidy’ mess, which reached its peak on his desk: everything that is normally stored in filing cabinets, index cards, address books and in a computer in an office, i.e. notes, letters, sketches, receipts, invoices, addresses, etc. was simply lying in layers on his desk! Not only did the ‘phenomenon’ immediately find what he was looking for on the visible layer, but, what was extraordinary, he knew that the address of a certain craftsman was written down on a piece of paper in a certain place on the table, a few layers below hundreds of other similar papers, and he pulled it out with ill-concealed satisfaction. Who does not feel a great nostalgia for such an extraordinary person? Fortunately, there is a lot of that left in Piero”.

Roberto Menghi, architect

(Livio Castiglioni and Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(Livio Castiglioni and Gio Ponti – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

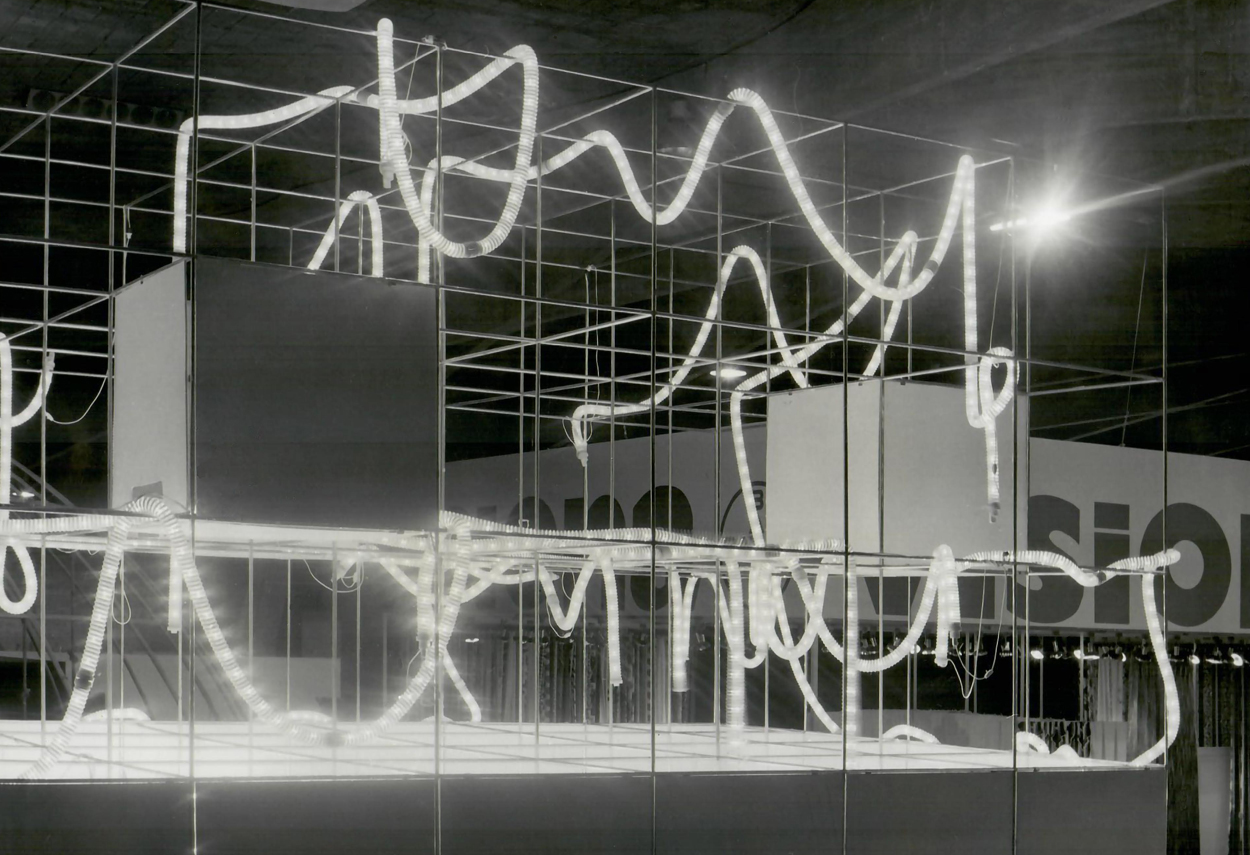

“It was the summer of 1964: Livio and I, invited to a fancy dress party, decided to rent, along with the costumes, two female wigs for the evening. When we arrived in Piazza San Babila, we decided to put the wigs on and triumphantly enter the square in an open-top spider under the astonished eyes of passers-by and traffic police. A few years later, in Capri, a solution had to be found to illuminate the swimming pool of a hotel; we were discussing it when my eye fell on a cleaner who was collecting leaves with a sort of hoover with a long flexible hose. It occurred to me that this long snake, suitably modified, could hold a long row of light bulbs and become a luminous object to be placed on the edges. Immediately, and as always enthusiastically, Livio started working on the idea, inventing modified ping-pong balls adapted to facilitate the joints in the tube and discussing with me all the technical solutions that would lead to the “Boalum”. Livio Castiglioni was at my side as a friend and collaborator for so much of that time, and so intensely, that even today I find I think back with regret to our moments of jokes and discussions, to the long trips up and down Italy, to his simplicity, intelligence and human charge. It was an intense and engaging energy in which the most disparate interests converged, held together by the desire to learn and experiment. Everyone knows what Livio Castiglioni represented in the history of design and lighting technology. Few people know that he was also a good photographer, amateur filmmaker and great lover of fireworks, which he never left behind, providing us with entertainment and lighting up the evenings with colourful flashes. A goliard by vocation, he demythologised his profession to the extent that in his house in Via Morosini he kept an incredible collection of kitsch objects which he assembled on a pillar in the centre of the living room, which we called “the infamous column”. But his work was dominated by rigour and the ability to invent from nothing, typical of great designers. And then he loved life, and this is perhaps the most beautiful memory and the most important legacy he left me and which will stay with me forever”.

Gianfranco Frattini, architect

(1972 – Turin Eurodomus 4 – Boalum Artemide lighting complex – Livio Castiglioni and Gianfranco Frattini – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1972 – Turin Eurodomus 4 – Boalum Artemide lighting complex – Livio Castiglioni and Gianfranco Frattini – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

“Bilbao 1976, more or less. Official lunch for the opening of an important furniture shop. Dozens of important-looking people sit at the sumptuously laid table. A very young Paco de Lucia plays an Andalusian guitar and dedicates sweet, virtuoso music to Cini Boeri. At the head of the table, a very elegant Livio Castiglioni stands with a glass of wine in his hand: his arm is just outstretched towards the guests who, politely, get up ready to listen to a brief speech, as is the custom in these cases, and to to toast that unknown gentleman who, from his tone, could be an ambassador. The music fades away. Livio prolongs the pause a little, with a barely sketched smile, the irresistible joke and, in the most obsequious of silences, says: “I don’t know about you, but I only drink red wine!”. Thunderous applause. Livio, with the big black Borsalino on his head, was irrepressibly attracted by the pleasure of generating amazement, as through artifices of various electricity, he gave new and amazing forms to light with the least possible structural complexity. At work, Livio, with two pairs of glasses lowered over his eyes and parked on his forehead, depending on the required focal length, looked like a portrait of Saul Steinberg. He talked about very complicated things, with the lightness of a storyteller, so much so that even I, who really didn’t know anything about it, seemed to wander familiarly, perfectly wired, inside the instability of neutrons. Like one who practices poetic transgression, he untangled the tangle of banalities to reduce concepts to an apparent and exhilarating ‘little’. Those thin silver chains with a quartz of light are the unsurpassed example of someone who knows how to create the maximum astonishment with the minimum of means. I remember Livio (Steinberg mask) as well as Bruno Munari (Timeless Angel): very sweet and inimitable inventors of lightning. Livio revealed the mystery of electricity to the world. He wove invisible cases to build starry skies, he red-hot resistances to reveal the sound of dilation, he projected the dots and lines of futurism in the form of light, he went through his existence like a juggler drawing arabesques of crackling electrons. His work was an apparent game. He made visible a surprising part of the invisible.”

Pierluigi Cerri, architect

(1942 – Russia during the war – Recovering incandescent lamp – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1942 – Russia during the war – Recovering incandescent lamp – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

“Dear Livio, forgive me if I have let too much time pass, but only now am I given the opportunity to write to you. The void you have left among friends, and in your profession of genius, has still not been filled by anyone. I often feel nostalgic about the time when we worked together, during the long nights before the inauguration of some exhibition we had planned together, and your good humour and the jokes you made to everyone and about everyone were our constant companion. I always remember the dinner in Paris where, between one glass of wine and another of wine, you invented incredible and unique solutions to animate the entrance to the Eurodomus that we had to make at the Triennale. In the end you came up with a solution that even forced me to turn to the Municipal Electricity Company to get the necessary energy (in industrial quantities) and to search all over Italy for kilometres of thin nikelchrome wire to make these hot wires dance in the air above the great staircase, creating unforeseeable emotions and risks for all visitors. And when, in an exhibition on the environment, you simulated variable weather situations inside the pavilions of Torino Esposizioni and made visitors run for shelter or umbrellas, convinced, given the impressive simulated reality of the situation, that a storm had broken out even inside the exhibition. In short, dear Livio, I miss you, and above all Milan is missing an architect like you who is sensitive, brilliant, not arrogant and likeable. I love you”.

Cesare Casati, architect

“Livio, brilliant, unpredictable, very funny friend. A polyglot, in Bilbao when he worked for me on a large showroom, he spoke his Spanish, which was a mixture of Genoese and Venetian, his French was Milanese enriched with strange accents, and his Italian was often a warm and friendly Milanese. He created custom lighting the ‘spark’ for my work and I am very proud of that. He taught me to play with light, and with him I realised what an important element it was in architecture. Generous in his genius, he would appear as soon as he was called and enthusiastically draw you into the invention of the moment. But he disappeared twenty years ago, so trivially, so accidentally, to the great sorrow of all of us who knew him”.

Cini Boeri, architect

(1973 – France – Paris – Louvre Museum – “45 years of Domus” – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1973 – France – Paris – Louvre Museum – “45 years of Domus” – Livio Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

“I met Livio every now and then in my husband’s study. We greeted each other, joked around, he always wore his personal hat and his particular style of handling. We didn’t see the family very often. But there was one episode that made me feel Livio was like an uncle from Italy. My husband never calls me when he’s out of Milan and I’ve got used to his way. It happened that Livio and my husband left for Jeddah for the building site of a hotel that was being finished. Days went by, and the day my husband was due to return had also passed. “Maybe he will call me,” I hoped to myself, “If something has happened, an authority will call. One evening, the phone rang (…) It was Livio. He said: “Tomoko, it’s Livio, don’t worry about Emanuele. The sheik took him away to show him his villa, or something like that, but he’ll be right back in Jeddah. If you need money or anything else, ask Cesare”. After that evening, Livio always called me to reassure me. (…) Those two evening phone calls made me feel happy and safe in Italy, as if it was the same land where I was born and grew up. I am so happy to have felt his affection: much, much time has passed, but I will never forget Livio’s sweet heart. From Heaven he will tell me “What nonsense you are saying!”.

Tomoko Ponzio, wife of engineer Emanuele Ponzio

(1979 – Jeddah – Big Chandelier for the lobby of the Meridien Hotel – Livio and Piero Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(1979 – Jeddah – Big Chandelier for the lobby of the Meridien Hotel – Livio and Piero Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

“Livio was the oldest but shared the eternal youth of the third, Achille. Livio had two vocations: that of a technician (who knows what he would have done if he had lived long enough to work “in” computers) and that of a designer, but the latter lived like a theatre director. He knew everything about techniques, especially those still unknown to others, but what he did was to criticise their coldness, their mere logic. So his imagination, not just fantasy, was not reduced to dressing up, but went into the systems for producing sound, light, images. And so often he was able to “bring out” those circuits, wires, connections and make them become objects, paradoxically de-technical. He began with the masterpiece that was the pre-war Phonola designed with Luigi Caccia Dominioni and Pier Giacomo (Achille, who had not yet graduated, did not yet sign his name): the 45° loudspeaker made it possible to listen to the radio placed on the table or attached to the wall; the speed of selection suggested the first digital controls in the history of radio. And Nizzoli certainly did not forget it when he designed the Lexicon ten years later. Later, with Frattini, the “Boalum” that, by carrying the light around the rooms, did violence to the conventions of the point-light, cancelling it. When it came to illuminate the grand staircase of the Triennale, he used the principle of the Watt regulator in the connection-detachment of cables – uncovered! – from which alternating light and darkness composed and revealed the design. Once he wanted to represent sound with light: thus, sound volume and light intensity grew and shrank together, symbolically and the occasion was ironic, but not towards design. For him, all technical factors were translated into sensorial ones, into functions favoured and stretched to the limit of the imagination, i.e. the intention to make the recipient overcome the mythology of technology. In this, although he came from a futurist climate, Livio was anti-futurist, a rationalist in his own way; of those who would like reason to be able to manage feelings too, but through signs intrinsic to the structure. Against those who the critics claim to have chosen irony to beat the arrogance of functionality – and with this, except for a few, often ended up throwing away design, its principles and sometimes even common sense – Livio chose irony towards the technique, although beloved, and against the easy banality of its results. Those who knew him know this to be true. They have also experienced it in their daily lives, in their traits, in their judgement of things. Livio was, with a few others, the champion of what can be defined as positive irony. A lesson that is not really over”.

Augusto Morello, Professor, President of ICSID

“One morning in late autumn many years ago, I saw architect Piero Castiglioni arrive in my workshop holding two pieces of wood that were not very long: one was serrated on one side and, pointing to the end, another shaped piece of wood that pretended to be a propeller. The other was a stick with a diameter of just over a centimetre. Without speaking, he stands in front of me and begins to rub the stick against the serrated part of the other piece. Mysteriously, the badly shaped piece of wood, the propeller, starts to turn. But that’s not all. By changing the angle of the serrated part and rubbing the stick, the propeller turns in the other direction. A bit of astonishment and wonderment and, after a pause, the architect began to speak: “but you are a “carpenter” and you will do it well, with the same care with which you do your own things”. The “Segavento” was born. The pieces of wood that Architect Livio Castiglioni had in his hands on a late autumn morning many years ago are kept in my workshop in a specially made box. This and many other ingenious ‘inventions’ in the field of furniture, often involving light, were the order of the day when working with the architect Castiglioni.

Pierluigi Ghianda

(Livio and Piero Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

(Livio and Piero Castiglioni – Photo courtesy: Piero Castiglioni)

Following in Livio’s footsteps is his son Piero, architect and designer, lively and intelligently active today, a point of reference for every theme/problem of light.

Bibliography:

(1) Courtesy Chiara Baldacci – Published on Flare – Architectural Lighting Magazine – n°22 – DECEMBER 1999 – page 78

(2) Anty Pansera. Dictionary of Italian Design, Milan, 1995, Cantini Editore

Other Posts